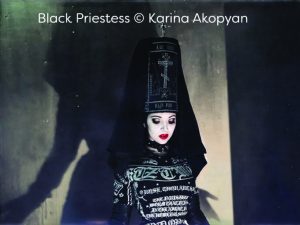

Karina Akopyan

TRUMAN BREWERY Unit 11, Dray Walk, Ely’s Yard, London E1 6QL 8th – 18th December 2016 (11am – 7pm daily)

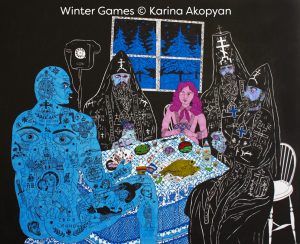

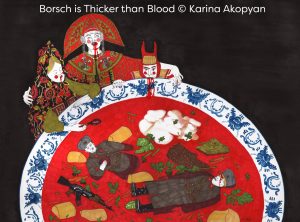

Martyrs & Matryoshkas is an exhibition of new and recent work by Russian-born, London-based artist Karina Akopyan. Featuring painting, photography, sculpture, installations and a selection of costume pieces, the series is a bold questioning of tradition, religion, ritual, iconography, sexuality and fetishism – in all their jarring coexistence yet inevitable convergence. Questioning the preservation of values and traditions, as either a beautiful necessity or, rather, a deceleration of progress, Akopyan poses this dilemma, with all its dichotomies, deceptions and implications, into the hands of the viewer.

The artist’s use of dark symbolism and sinister subject matter reveals similarities and contrasts between her strict Russian Orthodox heritage and the escapism of the London fetish scene, presenting us with a world of pain, euphoria, frustration, sexual fantasies, imagined memories, and secret aspirations. It is open to interpretation, evoking also the Jungian concept of the unconscious as a dynamic rebalancing of the rational psyche. In such a sense the oneiric symbols in Akopyan’s work form a mise-en-scène of the universal problems of birth, curiosity, grief, carnal temptation, sin, betrayal, pain, illness, search for enlightenment, purification and death.

The artist’s use of dark symbolism and sinister subject matter reveals similarities and contrasts between her strict Russian Orthodox heritage and the escapism of the London fetish scene, presenting us with a world of pain, euphoria, frustration, sexual fantasies, imagined memories, and secret aspirations. It is open to interpretation, evoking also the Jungian concept of the unconscious as a dynamic rebalancing of the rational psyche. In such a sense the oneiric symbols in Akopyan’s work form a mise-en-scène of the universal problems of birth, curiosity, grief, carnal temptation, sin, betrayal, pain, illness, search for enlightenment, purification and death.

“One of the themes that catalyzes my attraction to religion is concept of suffering or denial of things to yourself in order to reach humbleness. It’s a rather masochistic concept and this where it crosses with my interest in fetish.

“I would lie if I said I don’t like provoking emotions. Clear messages can be very boring. Why do you need to do all the work for the viewer? I think it’s much more fun to let people find their own interest or meaning in it. I like questioning ideas of normality; I like to think that every single one of us is completely different and unique. But my target is to open discussions and to get some feelings and emotions – hitting taboos often leads to that.” Karina Akopyan

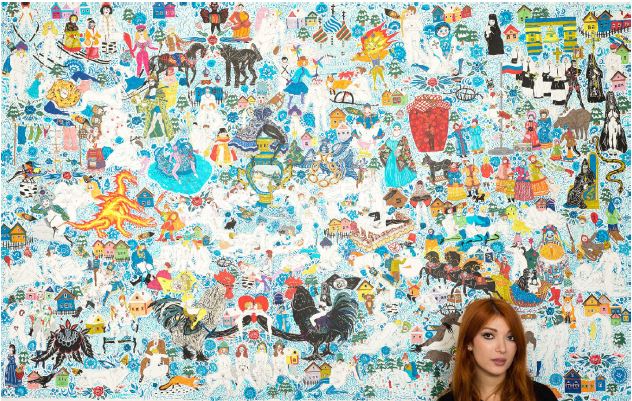

By investigating the link between patriotism and nationalism, she highlights the dilemma between the good and the bad patriot, and questions how identities are affected by the multiple understandings of ‘homeland’. Although on the surface appearing to turn exclusively to her motherland Russia as the focal point, she rejects that this belies any inherent hatred. In reality, much of her primary inspiration is in fact borne out of her love of the country’s artistic, literary, cinematic traditions and masterpieces.

Russian history is full of incredible characters and stories. And while the last 100 years may be the most obvious in her work, it reaches much further back, all the way into Kievan Rus, its pagan past, its folk tales and its superstitions. Akopyan’s work is a dissection a Russian spirit and a Russian character – touching upon the many elements from throughout Russian history that create its modern character. It is through this lens that the contentious questioning of Tradition comes through so strongly in Martyrs & Matryoshkas.

Russian history is full of incredible characters and stories. And while the last 100 years may be the most obvious in her work, it reaches much further back, all the way into Kievan Rus, its pagan past, its folk tales and its superstitions. Akopyan’s work is a dissection a Russian spirit and a Russian character – touching upon the many elements from throughout Russian history that create its modern character. It is through this lens that the contentious questioning of Tradition comes through so strongly in Martyrs & Matryoshkas.

Whether in painting, photography or a sculptural medium, her work is concerned primarily with self-analysis, towards what exists at the very origins of all we understand. In this sense, its entails a stripping down of every foundation to an essential core. She asks why we choose to hold on to the memories we do, why we interpret them in the way that we do, how they affect us and the scars they leave; she interrogates why we feel pain and desire, and – perhaps most importantly – why and how our perceptions of good and bad come to be.

When speaking of artistic influences, Akopyan refers to a diverse roster: Pierre Molinier, Louise Bourgeois, Marcel Dzama, Matthew Barney, Henry Darger, Nobuyoshi Araki, Egon Schiele, and, of course, Frida Kahlo, with her “artistic honesty” and ability to “bring to light all those emotions that these days seem to have fallen so out of fashion.” In literature, her influences are no less significant, from Russian folktales heard in childhood, to Nikolai Gogol, a 19C Russian writer of Ukrainian ethnicity dealing with topics surrounding superstition, and Mikhail Bulgakov, famed for The Master and Margarita.

Yet it is Russian cinema which seemingly ties Akopyan so strongly to her oeuvre – namely Andrei Tarkovsky:

“I don’t think my work would be anything close to what it is if I haven’t seen Tarkovsky’s films. His work changed my life more than any other artist.” KA

Nor are her influences purely Russian, or even Soviet. Alongside Tarkovsy and Parajanov stand such names as Stanley Kubrick, Francis Coppola, Ingmar Bergman, Jan Švankmajer and one of her favourite living directors, Chilean-French Alejandro Jodorowsky.

It is actually when we step momentarily away from a consideration of Russia, in Akopyan’s work, that the depth of interpretations can be more fully appreciated. Japanese influences, absorbed in her formal study of illustration and an immersion in the work of Aubrey Beardsley, who was himself heavily influenced by Japanese art, developed into obsessions with Japanese fetish art such as that by Toshio Saeki – bold, unapologetic and, in her loving meaning of the word, “twisted”.

“At some point I asked, if Japanese culture is fetishized like that, why can’t Russian culture be? I decided to become a love child of Toshio Saeki and Ivan Bilibin.” KA

Combined with a fascination with Mexican culture, one in which exists a love affair with death that is almost romantic and at the same time religious – marrying extremely violent imagery with Catholic imagery – a confluence can be triangulated upon which is despite its clear Russian edge at once religious, sexual, social, political and yet also universally human.

A new series of self-portrait photography works will also be exhibited. Intended to be seen alongside the paintings – and not separately – Akopyan uses them as an extension of the world that is perhaps more ‘fictionally’ described in her paintings. To the artist, there is an element of pure satisfaction in seeing one idea manifested in different ways; bringing a painting ‘to life’ makes it and its intrinsic concerns all the more immediate. Underlining this, the costumes and characters she projects in her self-portraits always first exist as small sections of, or details within, her painting.

“What matters is an idea; choice of media is not as important to me. Also because imagery and symbols are often reused, they sometimes find life in more than one medium over the course of time. I don’t really see separation between my paintings and photography – or any other medium I might use. I am just trying to tell a story. Sometimes I feel like I am in a perfectly blacked out room, feeling around for objects, textures and meanings, exploring more and more until I can finally put a picture of my imaginary surroundings together. Like some kind of blind puzzle.” KA

![Antigone [on strike] | Review Ali Hadji-Heshmati and Hiba Medina in Antigone [on strike] at Park Theatre, London. Photo: Nir Segal](https://theartiscapegallery.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/Antigone-on-strike-photo-by-Nir-Segal-D1_Standard-180x135.jpg)