“I wanted to lead the eye into spaces that hid, revealed, transformed all at one and where there could be some never-before-seen-image” (Dorothea Tanning).

Through Doorways, dreams

Bringing together 100 of Tanning’s works that span decades over multiple mediums from her enigmatic paintings, her lithographs to uncanny sculptures, this retrospective is the first large-scale exhibition of her work for 25 years and runs at Tate Modern until the 9th June 2019.

Born 25 August 1910, Galesburg, Illinois, United States, Dorothea Tanning first encountered surrealism in New York in the 1930s, a movement that emerged in Paris in the 1920s that explored the inner workings of the mind as sources of writing and imagery for art. In 1939 she

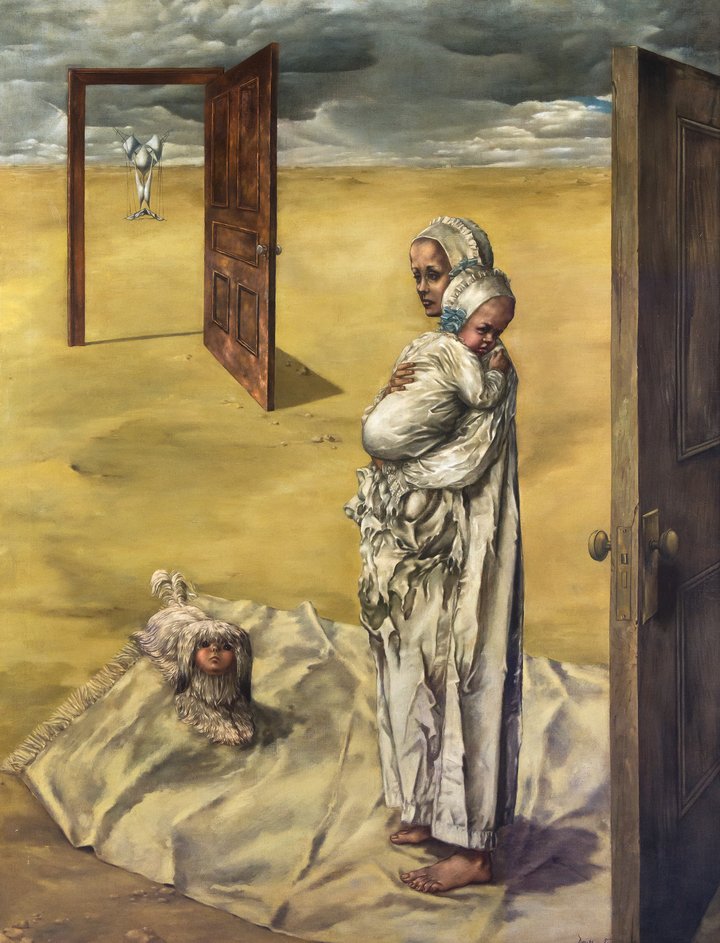

It was then in the 1940s, that Tanning’s powerful self-portrait Birthday 1942 would attract the attention of fellow prolific surrealist artist Max Ernst. The painting depicts Tanning as bare-breasted and shoeless. Ernst actually suggested the title to Tanning as to mark her birth into Surrealism.

Purchased with funds contributed by C. K. Williams, II, 1999 © DACS, London

They married in 1946 and settled in Sedona, Arizona where she painted his portrait, Max in a blue boat.

In the 50s Tanning returned to France with her husband.Working in Paris, Tanning’s paintings started to take on a more abstract form. Married until Ernst’s death in 1976, she never remarried.

In the 1960s, refusing to be put in a box by restricting herself to a single form of medium, she started making sculptures out of fabric. She used old fabrics to describe bodily form in her sculptures. An example of this at the exhibition is a room-sized installation Chambre 202, Hotel du Pavot 1970-3. In this sensual yet eerie

Dorothea Tanning (1910 – 2012)

Hôtel du Pavot, Chambre 202

1970-1973

Fabric, wool, synthetic fur, cardboard, and Ping-Pong balls

3405 x 3100 x 4700 mm

Centre Pompidou, Paris. Musée national d’art modern/ Centre de création industrielle Photo (C) Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Philippe Migeat

© DACS, 2019

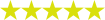

Tanning never had children yet the exhibition suggests maternity was on her mind. In Maternity 1946-1947 we see a woman cradling a child. A doorway leads to what looks to be female reproductive organs. A dog below has his face replaced by a human baby. Allegedly Tanning did not want children instead opting to lavish attention on her Pekinese dogs which we see represented in several of her paintings.

There is an unmistakable dreamlike quality to Tanning’s staggering body of work, combining the familiar with the strange while exploring desire and sexuality. She wanted to depict ‘unknown but knowable states’ suggesting there was more to life than meets the eye. She did not like when people interpreted her work as sexual preferring to refer to it as doorways to the

Her last collection of poems, Coming to That, was published at the age of 101. She leaves an amazing legacy of work.

Dorothea Tanning’s Exhibition runs until 9th of June at Tate Modern London. So not much time left to see it.

![Antigone [on strike] | Review Ali Hadji-Heshmati and Hiba Medina in Antigone [on strike] at Park Theatre, London. Photo: Nir Segal](https://theartiscapegallery.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/Antigone-on-strike-photo-by-Nir-Segal-D1_Standard-180x135.jpg)