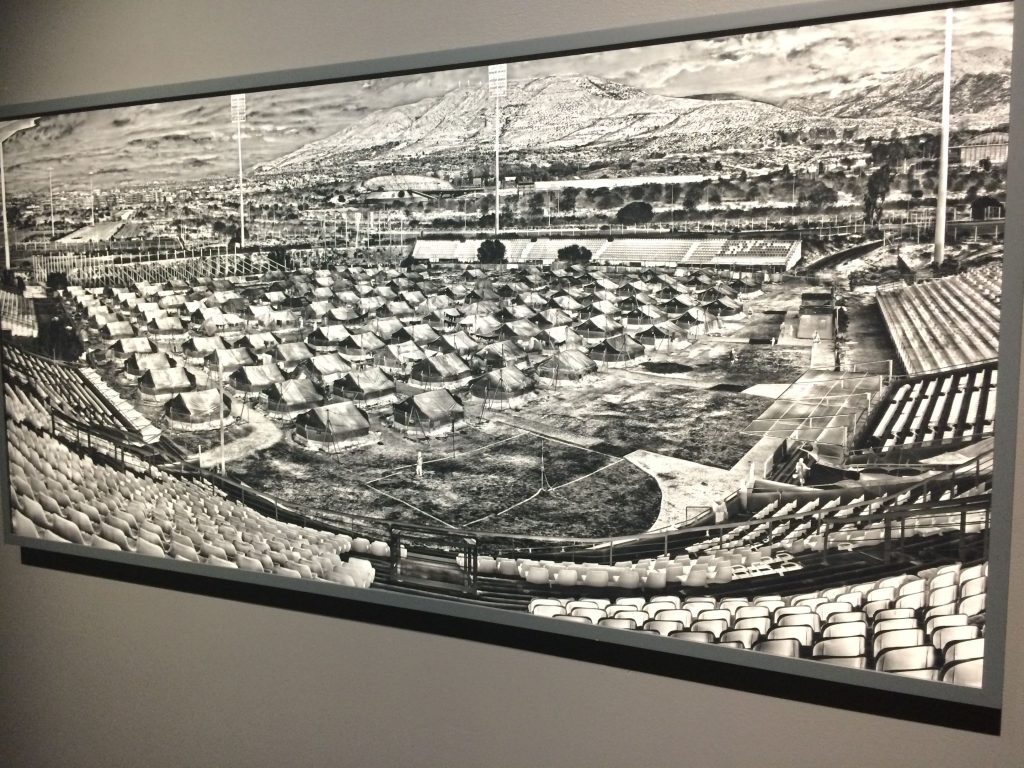

Conceptual artist Richard Mosse has been awarded the 2017 Prix Pictet for his Heat Maps, a series of panoramic images. They were shown at the highly acclaimed solo exhibition Incoming in the Curve Gallery, Barbican along with a film, a large scale three-screen video projection. Incoming charts the movement of refugees attempting to enter Europe from the Middle East and North Africa, through the lens of a military-grade, thermographic camera.

The camera is a powerful piece of surveillance equipment made in Britain for military use and designed for long distance warfare and border enforcement. Essentially, this is technology used to keep people out. It is capable of detecting the human figure by body heat from a distance of over 30km, day and night. International Traffic in Arms Regulations controls the export of thermal cameras, as they are classified as a weapon under international law.

Incoming turns the weapon against the purpose of surveillance to let the viewer into the disturbing reality of the European refugee crisis, through the cold lens of law enforcement. Channel 4 news anchor Jon Snow aptly called Incoming “perspective bending”.

The Artiscape went to the Barbican to see the exhibition. The eerie and ghost-like figures of refugees were projected across three large screens: the surrounding experience was entirely visceral; the film, soundscape, and imagery were harrowing and made for uncomfortable viewing.

On 15 February 2017, Richard Mosse was in discussion with cinematographer Trevor Tweeten, composer Ben Frost who collaborated on Incoming. Sophie Darlington, acclaimed British Wildlife Photographer moderated the discussion. It was she who first recommended to Mosse the thermographic camera used to make the work.

Back in April 2014, Mosse met Darlington in Brewer Street car park, London, UK. She had been shooting with the advanced thermal camera in the wildlife setting for a few years and had seen Mosse’s photographs of the war in the Eastern Congo using colour infrared film intended to create a new perspective on the conflict.

Darlington told him she had an idea for his next piece. “I had seen Richard’s work in Venice and thought this [thermal camera] is the perfect thing for him.”

The next day they met in a café and Darlington showed Mosse some of her footage: “this is the camera they used to make this [wildlife] piece and it is an extraordinary thing”, she told him.

Three years later, Darlington had just stepped off a plane from Antarctica after two months filming, when she got a phone call from Mosse to come and view the finished work at the Barbican. “I think you will all agree it’s just the most haunting visceral piece” said Darlington. She was delighted to be associated with it “… it is just exceptional,” added Darlington.

Filming the art took Mosse and his collaborators to some dangerous and off the grid conflict zones. Darlington quizzed Mosse on how they got access to film in some of the locations. “A documentarian’s life is about 95 percent bureaucracy and trying to get access [to areas], and 5 percent actually making the documentary. But in relation to the refugee crisis, a lot of it wasn’t that restricted; but some of it was”, he replied.

Their filming began on the shores of the Mediterranean and the Aegean Sea (ground zero for refugees seeking the route into Europe) and took them to Northern Niger and the Sahara Desert. This is Al Qaeda territory so the group’s only choice was to work with the Niger army that gave them an armed escort when working in the area. “They [the army] go in these enormous migrant convoys on a Sunday night, about one hundred trucks plus,” said Mosse.

“So that’s the footage of the swaying trucks… with the absolute humanity…” Sophie exclaimed.

At present, the refugee crisis is taking place across three continents and in many countries. Events happen in ways that are dislocated and very unpredictable. Mosse found making a schedule for the filming almost impossible. As they had to move on the fly, they soon discovered that capturing the movements of refugees depended on following daily news reports, building up networks of contacts in various countries and relying on tip-offs.

Incoming is composed of monochromatic stills Heat Maps and a film of roving footage with an unnerving soundscape. Images were shot with a long lens that reached far into the distance and with an invasive microscopic lens, which captured some of the macabre consequences of the humanitarian crisis, and some intimate moments amidst the chaos.

The team met fixer Daphne Tolis on the Greek Island of Lesbos, who then introduced them to a pathologist in Rhodes. This relationship resulted in the troubling scene of an autopsy being performed on a child’s corpse that had been washed up on a Mediterranean shore. The 11-year-old female had drowned off the Island of Leros and her body was taken to Rhodes for her DNA to be extracted so her identity could be put on a database.

“How were you allowed to film the autopsy? It’s not something I could palette,” asked Darlington.

“We were quite direct with him [the pathologist]: saying, this is an art project, we are not journalists and this isn’t news. We are interested in making a film using this particular camera. In fact, because of the nature of how it [the camera] sees (quite different from a normal camera) he really got behind it and was interested in letting us come in”, replied Trevor Tweeton.

The soundtrack adds a powerful dimension to the whole piece. Ben explained 75% was done in the field and another 25% back in the studio involving “a lot of reconstruction”. In some parts he explained, there were images but no sound. Another challenge for Ben was the decision by Trevor and Richard to slow the footage down.

There were other times in the film where it was “just soundtrack and voices” and no picture. In one such case, the sound makes for a very powerful tool, when rescuers were trying to resuscitate a drowning victim. This Ben explains “forces the viewer to put everything back together”, “to construct that reality”. The result is something all-consuming and harrowing.

At around four o’ clock in the morning, the Thermo camera picked up the poignant footage of a man washing his face before getting down on his hands and knees to pray. As an example of how far the camera could see into the distance, this scene was not visible to the naked eye from where the artists were standing. It was “an incredibly intimate moment that we had witnessed… very unselfconscious. The way we tried to translate it in the film, is that he [the praying man] is in the middle of all this chaos but he is still present in himself. He is coming from somewhere; he is going somewhere, but he doesn’t really know,” said Tweeton.

Mosse said that filming these intimate scenes with a regular camera would not have been possible in “good conscience”, as it would have been “too gratuitous”. Critics have likened his work to war reportage and he has become an influencer in the photojournalism tradition. Reporting conflict provides the greatest ethical challenges to journalists for upholding the humanity of all those involved while helping those on the outside to better understand the roots and reality of the conflict. Artists working in conflict zones also share this obligation to truth and fairness. Yet, unlike for journalists, the creative boundaries for artists are always wide open.

In the process of making the film, Mosse was to learn how the Thermo camera resisted attempts to bend with his artistic imagination: it “resists telling a story” and demands the artist to “negotiate with it” and inform “how it was to function and how it should work”. In this sense, Mosse and his team have achieved a work of art that speaks to truth in a visual language: Incoming creates “an emotional space” that delivers a deeper human reality that could not be reached with conventional methods of war reporting.

Co-written by Fiona Doyle and Bianca Pascall

Have you heard ‘In Conversation: Richard Mosse’ by Barbican Centre on #SoundCloud?

[rev_slider alias=”test”]